During the thirteen days from October 18-29, 1962, the world stood and watched as the United States and U.S.S.R. nearly entered into a war that could have resulted in a worldwide nuclear holocaust. The showdown resulted from the extraction of Soviet nuclear presence in Cuba in exchange for the removal of American atomic weapons in Turkey and a continued quarantine against Cuba, which is still in place to this day. There were many events during this thirteen-day period that nearly set off a war. Yet, thanks to the diligent decisions made by both President John F. Kennedy and Russian Premier Khrushchev, nuclear war was avoided.

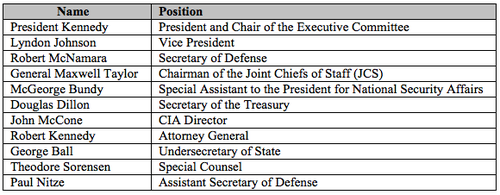

The Kennedy administration played a key roll in avoiding catastrophe by adhering to a process that considered all options, outcomes, and available information. To understand the decision-making process, we must first evaluate the people who were of influence. The Kennedy administration formed the Executive Committee (ExComm), “which brought together several N.S.C. members plus others who were not national security specialists but had the confidence of the president.” [1] There were 71 official members, but the most important are as follows:

To detail the input of each of these people would quickly fill a book, so for this paper’s practical purposes, we will focus on a few of the most influential and polarized members of the ExComm.

George Ball was the Under Secretary of State and a great advocate for the quarantine. He lobbied for caution in ordering any military action because there was no way to know what minor act could be enough to trigger the Soviets into launching a missile. Secretary Ball continuously held the position that any airstrike or invasion of Cuba might have irreversible consequences. He was a great critic of those who supported such ideas.

The Secretary of the Treasury was Douglas Dillon. Secretary Dillon was a man of significant influence and experience regarding international nuclear politics. Under the Eisenhower administration, Dillon served as the Ambassador to France, where he was the go-between while negotiating whether or not the U.S. would provide nuclear weapons in Vietnam to the French (which the U.S. refused to do). Secretary Dillon was very much in favor of military action in Cuba and advocated it as such.

Theodore Sorensen was Kennedy’s Chief of Staff responsible for drafting many of the president’s notes and speeches. If there was ever a man in a gate-keeping position between ExComm and the president, it was this man. Sorenson was in favor of the quarantine but was careful in keeping all options on the table.

The Assistant Secretary of Defense was Paul Nitze. Nitze was a believer in the American military superiority over Cuba and the Soviets. There is probably no doubt and was very eager to use military force to show the strength of the U.SU.S. He felt that not acting with force was to show weakness. He believed that the Russians would not enter a nuclear war because we greatly outnumbered and out strategized them on all nuclear capacity levels. He also headed the task force, which planned for a response to Soviet action in Berlin.

General Maxwell Taylor was the Army Chief of Staff and chairman of the J.C.S. He was a self-proclaimed hawk of ExComm and advocated military action in Cuba.

The most important three people in this decision-making process were Secretary of Defense McNamara, Special Assistant Bundy, and President Kennedy. Secretary McNamara, a Harvard graduate, was a brilliant strategist and understood the importance of institutional organization. He was an initial advocate for military action in Cuba. Still, after reviewing the situation and a few days of deliberation, McNamara switched to fully supporting the naval blockade. McNamara was one of Kennedy’s most trusted advisors and was extremely influential in encouraging Kennedy to stay the quarantine course. In his capacity as Secretary of Defense, McNamara’s primary role was to control the military and make sure they obeyed the naval blockade order with minimal action. Many military leaders were eager to execute military operations, but with McNamara’s superb leadership, he could restrain action.

McGeorge Bundy was the President’s Special Assistant for National Security Affairs. During the thirteen days of the Cuban Missile Crisis, Bundy switched his stance on what the most appropriate response to the Soviets was many times. Initially, he supported an airstrike, then the quarantine, and then exhibited passiveness to the whole situation. Although this was extremely frustrating to the president and members of ExComm, he served as an example of how no single option could be chosen without considering all possibilities, and that was important. Although Bundy could not settle on a choice, he did believe, “the choices were either direct military action, which he considered ‘intolerable,’ or learning ‘to live with Castro, and his Cuba,’ and adjust policies accordingly.” [2]

During the crisis, Bundy lobbied to respond to only the first letter (out of two) from Soviet Premier Khrushchev and ignore the second one altogether. He was also a voice supporting not publicly exchanging the U.S. missiles in Turkey for Cuba’s Soviet ones. He felt that if this information were made public, it would make the U.S. seem weak and hurt their NATO allies’ relations.

President John F. Kennedy was undoubtedly the most important figure on the U.S. side of the Cuban Missile Crisis. An experienced and well-versed politician, J.F.K. understood the importance of information gathering and moving cautiously forward in this delicate situation while all possible options could be considered. Kennedy had been in secret communications for months with the Soviets and had been explicitly promised that the Soviets would not ever build missile launch sites in Cuba. “When the president learned… about the character of the Soviet buildup, he felt both betrayed and politically threatened.” [3] Moving forward, Kennedy pulled together his most trusted and brightest advisors to form the ExComm, which would together find a way to resolve this issue peacefully.

As can be seen from these brief biographies of the most influential members of the ExComm, there was a diversity of specialists and opinions considered throughout the crisis. This diversity was part of what J.F.K. valued most in working through the decision-making process. The ExComm as a group had excellent access to outside information and consulted the U.N.U.N. and Congress on many issues. J.F.K. was not a biased leader on this issue, as can be gathered from his desire to have so much input and diversity of opinions. The ExComm had a realistic view of the situation and understood that making a wrong decision could end in a nuclear war, something to which no one is invulnerable. They also had a great base of experience from people who had dealt with international relations in the past, including current and past ambassadors.

It can be argued that the ExComm didn’t gather all the information which existed, but I think that they realized that fact and was a factor in the decision-making process. In learning that more information was out there to be gathered and that more options may present themselves given time, I believe that Kennedy opted for the quarantine because it bought time to collect more information. If a military action had been the first course of action, then the situation would have been outside the decision-makers’ control.

These people can be generally classified into two groups at the beginning of the crisis: hawks, who want U.S. military action in Cuba, and doves, who want to pursue diplomatic measures and implement a quarantine zone around Cuba. Some of these peoples’ initial beliefs change over the thirteen days, and in the end, it is the doves that win out. Over the next few pages, I will outline a brief timeline of the significant events during this 13-day period, which had a considerable impact on the decision-making process to implement and maintain the quarantine around Cuba instead of initiating military action.

Thirteen days passed from the onset of the Kennedy/ExComm involvement in the Cuban Missile Crisis, but the first reconnaissance photos of the missile launch sites were taken by a U-2 spy plane on October 15, 1962.

October 16 – Day 1 [4] President Kennedy receives news of the missile sites in Cuba while having breakfast. He immediately calls together his Ex-Comm to start discussing the American response to this news.

October 17 – Day 2 Kennedy meets with Soviet Foreign Minister Andrie Gromyko and informs him that the U.S. will not accept the presence of Soviet missiles in Cuba. This meeting is held in secret, and the public is not yet made aware that this situation exists.

October 18 – Day 3 Ex-Comm meets to discuss the situation, and many members polarize to recommendations of military action (airstrikes or invasion) or to enforce a naval blockade (quarantine). Dean Acheson initially supports military action, while Robert Lovette and McGeorge Bundy advise that a quarantine would be best. As conversations developed, many members of ExComm came to believe that the quarantine option was the best thing to do, at least for now and that any military action may be too rash and have irreversible, long-term consequences.

October 19 – Day 4 Balancing scheduled campaign appearances for the public with behind the scenes planning with ExComm, Kennedy leaves for Ohio and Illinois. Before going on his trip, Kennedy meets with Secretary of Defense McNamara and members of the Joint Chiefs of Staff (J.C.S.). The J.S.C. reports an initial agreement on an airstrike combined with a quarantine but expresses concern that there was no guarantee that all missile sites could be destroyed and the political repercussions could be significant.

Kennedy points out that to act in Cuba would justify a Soviet response in Berlin, which needed to be avoided at all cost. U.S. troops in Germany were not positioned to defend American interests there. Air Force Chief of Staff LeMay states that a quarantine without military action would be a sure step toward war and that military action was the only possibility. Kennedy refutes by saying that if we take action, the Soviets will too, and they are in too many superior positions in sensitive areas that we care about around the world, like Berlin.

October 20 – Day 5 Kennedy returns home early from the campaign under the excuse of an upper-respiratory infection so that he can meet with the ExComm and try to find a suitable alternative to military action.

October 21 – Day 6 This day is a turning point in the decision-making process. New intelligence gathered from a U-2 flight shows that there are many more missile sites along the northern shores of Cuba and fleets of Cuban bombers poised for an attack at a moment’s notice. Estimates show that 10-20 thousand casualties could result from airstrikes, and since not all of the missile sites could be taken out, there would undoubtedly be retaliation from the Soviets. Kennedy firmly decides on a naval blockade only for the time being.

October 22 – Day 7 In a meeting between J.F.K. and his brother, Robert Kennedy pledged his quarantine support. “I was one of the strongest backers of this strategy because it signaled our resolve but gave Khrushchev room to back down and increased the probability of achieving our objective without catastrophic military action.” [5]

President Kennedy addresses the public and informs the world of the situation and his decision to implement only a naval blockade with an impending military strike if further provoked by the Soviets. Many congressional members urge Kennedy to order airstrikes, but he does not. Kennedy sets the military alert level to DEFCON 3. All Cuban forces are mobilized in response and prepare to defend Cuba in the event of invasion.

October 23 – Day 8 The Organization of American States votes unanimously to support the naval blockade. With this support, Kennedy orders ships into place, and the siege is established by nightfall. McNamara reviews the plan to retaliate against Cuba and Soviet positions if an American plane is shot down while conducting reconnaissance flights. Kennedy agrees that any Surface to Air Missile (S.A.M.) site fires on an American aircraft will be destroyed, and a warning be issued that upon a second instance, the U.S. will destroy all Cuban S.A.M. sites. Bundy suggests that Kennedy relinquish authority to attack any S.A.M. site if deemed necessary by those in the field. Kennedy agrees under the condition that there is irrefutable evidence that a plane was shot down, not just crashed due to mechanical errors.

The president submits the official Quarantine Proclamation, which states the rules and justifications for the naval blockade. The ExComm anticipates that violence will break out when the U.S. tries to board a Soviet ship, but it is a risk they will have to take. Bundy disagrees with this, stating that the Soviet ships are small compared to ours, and resistance is not likely.

October 24 – Day 9 Soviet ships reach the quarantine line for the first time but hold their positions just outside the line as ordered by Moscow. Robert F. Kennedy (R.F.K.) and J.F.K. discuss the political implications of this situation. They agree that to have taken any less of action would have resulted in impeachment and that to take a more significant action could result in war. It seems that Khrushchev is happy that this could be an embarrassing situation for Kennedy before the forthcoming congressional elections. The Kennedys both believe that the Soviet ships will try to break the barricade, but they still are not sure what the best course of action in that instance would be.

Dean Rusk, J.F.K., and Senator Everett Dirksen meet with congressional leaders to discuss the implications the Cuban situation has on Berlin. Senate majority leader Mike Mansfield expresses concern that no military action is a small military action. Any forceful retaliation towards the Soviets will justify any equal action they may take in Berlin. He states that to attack Cuba is to give up Berlin, which no one in the Western World will tolerate.

October 25 – Day 10 The U.S. ambassador to the UN, Adlai Stevenson, confronts the Soviet delegates about the situation, but they refuse to discuss it. Kennedy changes the military alert to DEFCON 2, the highest it has ever been in U.S. history. “Unprecedented actions were taken by the U.S. Strategic Air Command (S.A.C.). S.A.C. was generated to still higher alert, DEFCON 2, for the first time, on October 25.” [6]

U.N.U.N. Secretary-General U Thant proposes that “there should be a voluntary suspension on behalf of Russia to all arms shipments to Cuba and at the same time a suspension of the quarantine measures involving the search of ships.” [7]

Kennedy refuses this proposal and will not consider any such action so long as the missiles are still active.

A tanker ship, the Bucharest, approached the quarantine line, and ExComm starts discussions on what the consequence of allowing it to pass unchallenged would be. After a U.S. destroyer blocks it, it proves that it carries no cargo restricted under the quarantine and is allowed to continue to Cuba with a U.S. escort ship. The question arises of the significance of this, and it is decided that a Soviet ship will have to be stopped and restricted sometime soon to prove that the quarantine is real.

McNamara and Kennedy both believe that permitting this ship’s passage does not weaken their stance because it was deemed within the restrictions to pass, but both feel that a boat with offensive weapons needs to get stopped to show the U.S. means business.

J.F.K. states that the quarantine could be lifted if the U.N.U.N. could guarantee that no new missile materials be delivered to Cuba. Bundy and McNamara strongly oppose this because the missiles that are already there would still be active, which is unacceptable. Kennedy agrees with this point and, from this day on, refuses to accept any negotiations which do not include the dismemberment of all missiles in Cuba.

The final order of business for the day is that P.O.L. (petroleum, oil, and lubricants) be added to the restriction list in Cuba because of these materials aid in building and completing the missile sites.

October 26 – Day 11 Soviet Premier Khrushchev sends a letter to President Kennedy stating that he would dismantle his Cuban-based missiles if the U.S. would publicly promise not to invade Cuba. Khrushchev also proposes that the U.S. should remove its missiles from Turkey. R.F.K. and Soviet Ambassador Dobrynin meet secretly and, with permission from J.F.K., decide that the removal of Turkey-based US missiles is an excellent negotiating platform.

Simultaneously, Fidel Castro of Cuba sends a message to the Soviet Premier requesting a nuclear strike against the U.S. in retaliation for a US-led invasion of Cuba. Secretary Dillon reaffirms his belief that an airstrike against Cuba is still in order and a far better alternative to a sea-based confrontation.

J.F.K. asks for the U.S. ambassador to the U.N.’sU.N.’s opinion on how to proceed with this issue in the U.NU.N. Ambassador Stevenson responds with a two-part plan. First, all parties involved should agree to a three-day standstill where there would be no naval action in the Gulf. During these days, the progress in building the missiles would cease, and they would remain inactive. Second, negotiations could thus continue, and Cuba would need to agree to complete removal of their presence in Cuba, guaranteeing no anti-Cuban action, and being flexible in removing Turkish-based missile sites.

C.I.A. Director John McCone argues that under no circumstances should the quarantine around Cuba be dropped as part of the negotiation.

Kennedy finds the middle ground, “Well now, the quarantine itself won’t remove the weapons. So you only get two ways of removing the weapons: one is negotiating them out, in other words, trade them out, and the other is to go in and take them out. I don’t see any other way you’re going to get the weapons out” [8]

October 27 – Day 12 A U-2 spy plane is shot down over Cuba, but despite the earlier decision about the S.A.M. site, J.F.K. did not issue a strike order. On this same day, the C.I.A. reports that at least five M.R.B.M. missiles are fully operational in Cuba. ”Later evidence indicated that some of the M.R.B.M.s were indeed ready to fire by October 21 and that all of them were ready to fire by October 27.” [9]

Khrushchev announces publicly that he is willing to peacefully trade the Soviet missiles in Cuba for the U.S. ones in Turkey. This forces the Kennedy Administration to make a final decision. Many members of the ExComm agree that taking any military action in the light of a peaceful solution would not be looked well upon by the public. To be on the brink of nuclear war and do anything that might push the situation over the edge when being offered a peaceful way out would be an unreasonable decision. Since the Russians first publicly shown these reasonable terms for peace, breaking away from this offer would allow the Soviets to move on Berlin and justify it since they could claim they were not the aggressor.

October 28 – Day 13 An agreement is made between the U.S. and the U.S.S.R., which states the U.S. will not invade Cuba U.S. will remove its missiles from Turkey within a reasonable amount of time. In exchange, the Soviets agree to remove all of their nuclear assets from Cuba and allow for U.N.U.N. supervision of the missile dismantling. Cuba also agrees not to publicly announce that the missiles in Turkey were a part of the deal.

Premier Khrushchev makes a radio address in Moscow stating that he will remove Soviet presence from Cuba. He fails to mention any trade-in regarding Turkey, and the Cuban Missile Crisis comes to an end.

Nuclear war has been avoided, and the U.S. has triumphed over the Soviets. The decision-making process in the Kennedy administration had once fallen to the harmful outcomes associated with Group Think. Still, after the Bay of Pigs incident, J.F.K. revamped his decision-making process to encourage dissent and critical evaluation among his team. In the Cuban missile crisis, virtually the same policymakers produced superior results.” [10] It seems that had the Bay of Pigs fiasco not occurred, the Cuban Missile Crisis’s outcome may have been much different, and the earlier sentiments to apply force in Cuba may have had a better chance at occurring.

In Conclusion, the Cuban Missile Crisis brought the U.S. dangerously close to nuclear war with the Soviets. Still, with some diligent decisions and actions, the world was spared this worst-case scenario. The analysis of whether this was the best process is a whole other topic, but it can be argued that continuing to punish Cuba for its involvement in this crisis is excessive and unjust. Whichever way you may feel about Cuba’s treatment, it should be agreed on by everyone that it is a small cost to pay for avoiding a nuclear holocaust.

WORKS CITED

- Barrett, David M., and Christopher Ryan. “5 National Security,” In The Executive Office of the President: A Historical, Biographical, and Bibliographical Guide. Edited by Relyea, Harold C., null22-null23. Westport, CT: Greenwood Press, 1997.

- The Cuban Crisis of 1962: Selected Documents and Chronology. Edited by David L. Larson. Boston: Houghton Mifflin, 1963.

- Freedman, Lawrence. _ Kennedy’s Wars: Berlin, Cuba, Laos, and Vietnam_. New York: Oxford University Press, 2000.

- Garthoff, Raymond L. Reflections on the Cuban Missile Crisis. Rev. ed. Washington, DC: The Brookings Institution, 1989.

- Harper, Paul, and Joann P. Krieg, eds. John F. Kennedy: The Promise Revisited. New York: Greenwood Press, 1988.

- Irving, L. Janis. _ “Groupthink,”_ Psychology Today. November 1971. Boston: Houghton Mifflin Company, 1972.

- Roger Hilsman, The Cuban Missile Crisis The Struggle over Policy. Westport, CT: Praeger Publishers, 1996.

- Mcnamara, Robert S., and James G. Blight. _ Wilson’s Ghost: Reducing the Risk of Conflict, Killing, and Catastrophe in the 21st Century_. New York: Public Affairs, 2001.

- Needler, Martin C. The Concepts of Comparative Politics. Westport, CT: Praeger, 1991.

- “The Cuban Missile Crisis”; available from https://www.hpol.org/jfk/cuban/; Internet; accessed December 2, 2005.

Footnotes

- David M. Barrett, and Christopher Ryan, “5 National Security,” in The Executive Office of the President: A Historical, Biographical, and Bibliographical Guide, ed. Harold C. Relyea (Westport, CT: Greenwood Press, 1997), 190. 2. Lawrence Freedman, _ Kennedy’s Wars: Berlin, Cuba, Laos, and Vietnam_ (New York: Oxford University Press, 2000), 161.

- Paul Harper and Joann P. Krieg, eds., John F. Kennedy: The Promise Revisited (New York: Greenwood Press, 1988), 90. 4. Unless otherwise noted, all of the information on this timeline was extracted from audio-recordings and transcripts from meetings in the White House, made available by the John F. Kennedy Presidential Library. Recordings and Transcripts are available at https://www.hpol.org/jfk/cuban/ 5. Robert S. Mcnamara, and James G. Blight, _ Wilson’s Ghost: Reducing the Risk of Conflict, Killing, and Catastrophe in the 21st Century_ (New York: Public Affairs, 2001), 47.

- Raymond L. Garthoff, Reflections on the Cuban Missile Crisis, Rev. ed. (Washington, DC: The Brookings Institution, 1989), 61. 7. The Cuban Crisis of 1962: Selected Documents and Chronology, ed. Larson, David L. (Boston: Houghton Mifflin, 1963), 125. 8. ”The Cuban Missile Crisis”; available from https://www.hpol.org/jfk/cuban/; Internet; accessed December 2, 2005. 9. Roger Hilsman, The Cuban Missile Crisis The Struggle over Policy (Westport, CT: Praeger Publishers, 1996), 104. 10. Irving L. Janis. _ “Groupthink,” Psychology Today._ November 1971, 43-44, 46, 74-76 Boston: Houghton Mifflin Company, 1972.